as you read, note what each program or law did or was intended to do

Tibetan musical score from the 19th century

Sail music is a handwritten or printed class of musical notation that uses musical symbols to indicate the pitches, rhythms, or chords of a vocal or instrumental musical piece. Like its analogs – printed books or pamphlets in English, Arabic, or other languages – the medium of canvass music typically is paper (or, in before centuries, papyrus or parchment). Although the access to musical annotation since the 1980s has included the presentation of musical notation on estimator screens and the development of scorewriter computer programs that tin notate a song or slice electronically, and, in some cases, "play dorsum" the notated music using a synthesizer or virtual instruments.

The use of the term "sheet" is intended to differentiate written or printed forms of music from sound recordings (on vinyl record, cassette, CD), radio or Television broadcasts or recorded live performances, which may capture motion-picture show or video footage of the functioning besides as the audio component. In everyday use, "sail music" (or simply "music") can refer to the print publication of commercial canvas music in conjunction with the release of a new pic, Boob tube prove, record album, or other special or popular issue which involves music. The first printed canvas music made with a printing printing was fabricated in 1473.

Sheet music is the basic form in which Western classical music is notated then that it can exist learned and performed by solo singers or instrumentalists or musical ensembles. Many forms of traditional and pop Western music are commonly learned past singers and musicians "by ear", rather than past using sheet music (although in many cases, traditional and pop music may also be available in sheet music form).

The term score is a common alternative (and more generic) term for sheet music, and in that location are several types of scores, every bit discussed below. The term score can also refer to theatre music, orchestral music or songs written for a play, musical, opera or ballet, or to music or songs written for a television programme or flick; for the terminal of these, see Motion-picture show score.

Elements [edit]

Title and credit [edit]

Sheet music from the 20th and 21st century typically indicates the title of the vocal or composition on a title folio or cover, or on the pinnacle of the first page, if in that location is no title folio or comprehend. If the song or piece is from a picture show, Broadway musical, or opera, the title of the chief work from which the song/piece is taken may be indicated.

If the songwriter or composer is known, their name is typically indicated along with the title. The sheet music may also indicate the name of the lyric-author, if the lyrics are by a person other than i of the songwriters or composers. It may also the proper name of the arranger, if the vocal or piece has been bundled for the publication. No songwriter or composer proper noun may be indicated for sometime folk music, traditional songs in genres such as blues and bluegrass, and very erstwhile traditional hymns and spirituals, considering for this music, the authors are often unknown; in such cases, the word Traditional is oftentimes placed where the composer's name would commonly go.

Title pages for songs may have a picture illustrating the characters, setting, or events from the lyrics. Title pages from instrumental works may omit an illustration, unless the work is program music which has, past its title or section names, associations with a setting, characters, or story.

Musical annotation [edit]

The type of musical notation varies a great bargain by genre or style of music. In near classical music, the melody and accompaniment parts (if present) are notated on the lines of a staff using round note heads. In classical sheet music, the staff typically contains:

- a clef, such as bass clef

or treble clef

or treble clef

- a cardinal signature indicating the fundamental—for instance, a cardinal signature with iii sharps

is typically used for the central of either A major or F ♯ minor

is typically used for the central of either A major or F ♯ minor - a time signature, which typically has 2 numbers aligned vertically with the bottom number indicating the note value that represents one shell and the top number indicating how many beats are in a bar—for case, a time signature of 2

4 indicates that in that location are two quarter notes (crotchets) per bar.

Most songs and pieces from the Classical flow (ca. 1750) onward indicate the piece's tempo using an expression—often in Italian—such as Allegro (fast) or Grave (irksome) as well as its dynamics (loudness or softness). The lyrics, if present, are written almost the melody notes. Nevertheless, music from the Baroque era (ca. 1600–1750) or earlier eras may have neither a tempo marking nor a dynamic indication. The singers and musicians of that era were expected to know what tempo and loudness to play or sing a given song or slice due to their musical experience and knowledge. In the contemporary classical music era (20th and 21st century), and in some cases before (such as the Romantic menses in German-speaking regions), composers often used their native language for tempo indications, rather than Italian (e.k., "fast" or "schnell") or added metronome markings (e.g., ![]() = 100 beats per minute).

= 100 beats per minute).

These conventions of classical music note, and in particular the apply of English language tempo instructions, are likewise used for sheet music versions of 20th and 21st century popular music songs. Popular music songs often indicate both the tempo and genre: "slow dejection" or "uptempo rock". Pop songs often contain chord names in a higher place the staff using letter names (east.g., C Maj, F Maj, G7, etc.), and so that an acoustic guitarist or pianist can improvise a chordal accompaniment.

In other styles of music, different musical notation methods may be used. In jazz, for example, while nigh professional performers can read "classical"-manner notation, many jazz tunes are notated using chord charts, which bespeak the chord progression of a song (e.g., C, A7, d minor, G7, etc.) and its grade. Members of a jazz rhythm department (a piano actor, jazz guitarist and bassist) apply the chord nautical chart to guide their improvised accessory parts, while the "lead instruments" in a jazz grouping, such as a saxophone player or trumpeter, utilize the chord changes to guide their solo improvisation. Like pop music songs, jazz tunes often indicate both the tempo and genre: "tiresome dejection" or "fast bop".

Professional country music session musicians typically utilise music notated in the Nashville Number Organization, which indicates the chord progression using numbers (this enables bandleaders to change the key at a moment'south discover). Chord charts using letter names, numbers, or Roman numerals (east.g., I–IV–V) are as well widely used for notating music by blues, R&B, rock music and heavy metal musicians. Some chord charts practice not provide any rhythmic information, but others use slashes to indicate beats of a bar and rhythm notation to betoken syncopated "hits" that the songwriter wants all of the band to play together. Many guitar players and electric bass players learn songs and note tunes using tablature, which is a graphic representation of which frets and strings the performer should play. "Tab" is widely used by rock music and heavy metal guitarists and bassists. Singers in many pop music styles learn a song using only a lyrics canvas, learning the melody and rhythm "by ear" from the recording.

Purpose and utilize [edit]

Sheet music can be used as a tape of, a guide to, or a means to perform, a song or piece of music. Sail music enables instrumental performers who are able to read music notation (a pianist, orchestral musical instrument players, a jazz band, etc.) or singers to perform a vocal or piece. Music students use sheet music to learn about different styles and genres of music. The intended purpose of an edition of sheet music affects its design and layout. If sheet music is intended for study purposes, as in a music history class, the notes and staff can exist made smaller and the editor does not take to be worried about page turns. For a functioning score, however, the notes have to be readable from a music stand and the editor has to avoid excessive page turns and ensure that any folio turns are placed afterwards a rest or pause (if possible). As well, a score or part in a thick bound book will non stay open, and so a performance score or part needs to be in a thinner binding or employ a binding format which will lay open up on a music stand.

In classical music, authoritative musical information about a piece can be gained by studying the written sketches and early versions of compositions that the composer might have retained, as well as the last autograph score and personal markings on proofs and printed scores.

Comprehending canvass music requires a special form of literacy: the ability to read music annotation. An power to read or write music is non a requirement to compose music. In that location accept been a number of composers and songwriters who have been capable of producing music without the capacity themselves to read or write in musical annotation, as long as an amanuensis of some sort is available to write down the melodies they think of. Examples include the blind 18th-century composer John Stanley and the 20th-century songwriters Lionel Bart, Irving Berlin and Paul McCartney. As well, in traditional music styles such as the blues and folk music, there are many prolific songwriters who could not read music, and instead played and sang music "past ear".

The skill of sight reading is the ability of a musician to perform an unfamiliar work of music upon viewing the canvass music for the start time. Sight reading ability is expected of professional person musicians and serious amateurs who play classical music, jazz and related forms. An even more refined skill is the ability to look at a new slice of music and hear near or all of the sounds (melodies, harmonies, timbres, etc.) in one's head without having to play the piece or hear it played or sung. Skilled composers and conductors have this power, with Beethoven being a noted historical example. Not everyone has that specific skill. For some people music sheets are meaningless, whereas others may view them equally melodies and a form of art. As Jodi Picoult, an American writer once said in her novel entitled "my sister'southward keeper", "information technology'due south like picking up an unfamiliar piece of sheet music & starting to stumble through it, only to realize information technology is a melody you'd once learned by heart, 1 y'all can play without even trying."

Classical musicians playing orchestral works, sleeping accommodation music, sonatas and singing choral works ordinarily have the sheet music in front of them on a music stand up when performing (or held in forepart of them in a music folder, in the case of a choir), with the exception of solo instrumental performances of solo pieces, concertos, or solo vocal pieces (art song, opera arias, etc.), where memorization is expected. In jazz, which is by and large improvised, canvas music (chosen a atomic number 82 sheet in this context) is used to give basic indications of melodies, chord changes, and arrangements. Even when a jazz band has a pb canvass, chord nautical chart or bundled music, many elements of a performance are improvised.

Handwritten or printed music is less important in other traditions of musical practice. Nonetheless, such as traditional music and folk music, in which singers and instrumentalists typically acquire songs "by ear" or from having a song or tune taught to them by another person. Although much popular music is published in annotation of some sort, information technology is quite common for people to learn a song by ear. This is as well the example in most forms of western folk music, where songs and dances are passed down by oral – and aural – tradition. Music of other cultures, both folk and classical, is often transmitted orally, though some non-Western cultures developed their ain forms of musical notation and sail music as well.

Although sheet music is oft thought of as being a platform for new music and an aid to limerick (i.e., the composer "writes" the music down), information technology tin can also serve every bit a visual tape of music that already exists. Scholars and others have made transcriptions to render Western and non-Western music in readable form for study, analysis and re-creative performance. This has been washed not but with folk or traditional music (e.g., Bartók's volumes of Magyar and Romanian folk music), merely also with audio recordings of improvisations by musicians (east.1000., jazz piano) and performances that may only partially be based on note. An exhaustive example of the latter in recent times is the collection The Beatles: Complete Scores (London: Wise Publications, 1993), which seeks to transcribe into staves and tablature all the songs equally recorded by the Beatles in instrumental and vocal detail.

Types [edit]

Modern canvass music may come in different formats. If a piece is composed for just 1 instrument or voice (such as a piece for a solo instrument or for a cappella solo voice), the whole piece of work may exist written or printed as one piece of canvass music. If an instrumental piece is intended to be performed by more than one person, each performer will usually have a dissever piece of sheet music, called a part, to play from. This is specially the case in the publication of works requiring more four or so performers, though invariably a full score is published as well. The sung parts in a song piece of work are not usually issued separately today, although this was historically the example, especially before music printing made sail music widely available.

Sheet music can be issued every bit individual pieces or works (for example, a popular song or a Beethoven sonata), in collections (for instance works by one or several composers), as pieces performed by a given artist, etc.

When the separate instrumental and vocal parts of a musical work are printed together, the resulting sheet music is called a score. Conventionally, a score consists of musical notation with each instrumental or vocal part in vertical alignment (meaning that concurrent events in the notation for each role are orthographically arranged). The term score has also been used to refer to sail music written for just one performer. The stardom between score and part applies when there is more than one function needed for performance.

Scores come in various formats.

Total scores, variants, and condensations [edit]

A full score is a large book showing the music of all instruments or voices in a composition lined up in a fixed order. It is large enough for a usher to be able to read while directing orchestra or opera rehearsals and performances. In addition to their applied utilize for conductors leading ensembles, full scores are as well used by musicologists, music theorists, composers and music students who are studying a given piece of work. Nosotros distinguish different scores;

A miniature score is like a total score simply much reduced in size. Information technology is as well pocket-sized for use in a performance by a usher, but handy for studying a piece of music, whether information technology be for a large ensemble or a solo performer. A miniature score may comprise some introductory remarks.

A study score is sometimes the same size as, and oft indistinguishable from, a miniature score, except in name. Some study scores are octavo size and are thus somewhere between full and miniature score sizes. A study score, especially when part of an anthology for bookish study, may include extra comments almost the music and markings for learning purposes.

A pianoforte score (or piano reduction) is a more than or less literal transcription for piano of a slice intended for many performing parts, especially orchestral works; this can include purely instrumental sections within large vocal works (see vocal score immediately below). Such arrangements are made for either piano solo (2 hands) or piano duet (1 or two pianos, 4 easily). Extra modest staves are sometimes added at certain points in piano scores for two hands to make the presentation more consummate, though information technology is unremarkably impractical or impossible to include them while playing.

As with vocal score (below), information technology takes considerable skill to reduce an orchestral score to such smaller forms considering the reduction needs to exist non only playable on the keyboard but also thorough enough in its presentation of the intended harmonies, textures, figurations, etc. Sometimes markings are included to show which instruments are playing at given points.

While piano scores are usually not meant for performance outside of written report and pleasance (Franz Liszt'south concert transcriptions of Beethoven's symphonies being one group of notable exceptions), ballets get the most applied benefit from pianoforte scores because with one or two pianists they allow the ballet to do many rehearsals at a much lower cost, earlier an orchestra has to be hired for the terminal rehearsals. Piano scores can as well exist used to train commencement conductors, who can conduct a pianist playing a piano reduction of a symphony; this is much less costly than conducting a full orchestra. Piano scores of operas do not include separate staves for the vocal parts, but they may add the sung text and phase directions above the music.

A part is an extraction from the full score of a particular musical instrument'due south part. It is used past orchestral players in performance, where the full score would be too cumbersome. However, in practice, it can be a substantial document if the piece of work is lengthy, and a detail instrument is playing for much of its duration.

Vocal scores [edit]

A vocal score (or, more properly, pianoforte-song score) is a reduction of the full score of a vocal piece of work (e.chiliad., opera, musical, oratorio, cantata, etc.) to show the vocal parts (solo and choral) on their staves and the orchestral parts in a piano reduction (usually for two hands) underneath the vocal parts; the purely orchestral sections of the score are likewise reduced for piano. If a portion of the piece of work is a cappella, a piano reduction of the song parts is often added to aid in rehearsal (this oft is the instance with a cappella religious sail music).

Pianoforte-vocal scores serve as a user-friendly mode for song soloists and choristers to learn the music and rehearse separately from the orchestra. The vocal score of a musical typically does not include the spoken dialogue, except for cues. Piano-vocal scores are used to provide piano accessory for the performance of operas, musicals and oratorios by apprentice groups and some small-scale-scale professional groups. This may be done by a unmarried piano role player or by two piano players. With some 2000s-era musicals, keyboardists may play synthesizers instead of piano.

The related but less common choral score contains the choral parts with reduced accessory.

The comparable organ score exists likewise, usually in association with church music for voices and orchestra, such as arrangements (by later hands) of Handel'due south Messiah. It is like the piano-vocal score in that it includes staves for the vocal parts and reduces the orchestral parts to exist performed by one person. Unlike the vocal score, the organ score is sometimes intended past the arranger to substitute for the orchestra in performance if necessary.

A collection of songs from a given musical is usually printed under the label vocal selections. This is unlike from the vocal score from the same show in that it does not nowadays the complete music, and the piano accompaniment is usually simplified and includes the melody line.

Other types [edit]

A short score is a reduction of a piece of work for many instruments to just a few staves. Rather than composing directly in full score, many composers work out some type of brusk score while they are composing and subsequently expand the consummate orchestration. An opera, for example, may be written first in a short score, and so in full score, then reduced to a vocal score for rehearsal. Brusk scores are often non published; they may exist more than common for some performance venues (e.g., band) than in others. Because of their preliminary nature, brusk scores are the master reference point for those composers wishing to attempt a 'completion' of another's unfinished work (e.m. Movements 2 through 5 of Gustav Mahler'south tenth Symphony or the third act of Alban Berg'southward opera Lulu).

An open score is a score of a polyphonic piece showing each voice on a separate staff. In Renaissance or Baroque keyboard pieces, open up scores of 4 staves were sometimes used instead of the more mod convention of one staff per hand.[one] It is also sometimes synonymous with full score (which may have more than one office per staff).

Scores from the Baroque menses (1600-1750) are very oft in the form of a bass line in the bass clef and the melodies played past instrument or sung on an upper stave (or staves) in the treble clef. The bass line typically had figures written above the bass notes indicating which intervals in a higher place the bass (east.yard., chords) should be played, an approach chosen figured bass. The figures indicate which intervals the harpsichordist, pipe organist or lute player should play above each bass note.

The atomic number 82 canvass for the song "Trifle in Pyjamas" shows just the melody and chord symbols. To play this song, a jazz band's rhythm section musicians would improvise chord voicings and a bassline using the chord symbols. The lead instruments, such as sax or trumpet, would improvise ornaments to make the melody more interesting, then improvise a solo role.

Popular music [edit]

A pb sheet specifies simply the melody, lyrics and harmony, using ane staff with chord symbols placed higher up and lyrics below. It is usually used in popular music and in jazz to capture the essential elements of vocal without specifying the details of how the song should be bundled or performed.

A chord chart (or simply, chart) contains footling or no melodic information at all only provides fundamental harmonic information. Some chord charts also indicate the rhythm that should exist played, especially if there is a syncopated series of "hits" that the arranger wants all of the rhythm section to perform. Otherwise, chord charts either leave the rhythm bare or indicate slashes for each beat.

This is the most mutual kind of written music used past professional session musicians playing jazz or other forms of pop music and is intended for the rhythm section (usually containing pianoforte, guitar, bass and drums) to improvise their accompaniment and for whatsoever improvising soloists (eastward.g., saxophone players or trumpet players) to use as a reference indicate for their extemporized lines.

A imitation book is a collection of jazz songs and tunes with just the basic elements of the music provided. There are two types of fake books: (1) collections of lead sheets, which include the melody, chords, and lyrics (if present), and (2) collections of songs and tunes with only the chords. Simulated books that contain only the chords are used by rhythm section performers (notably chord-playing musicians such as electrical guitarists and piano players and the bassist) to help guide their improvisation of accompaniment parts for the song. False books with only the chords can also be used by "atomic number 82 instruments" (e.g., saxophone or trumpet) every bit a guide to their improvised solo performances. Since the melody is not included in chord-only imitation books, lead musical instrument players are expected to know the tune.

A tablature (or tab) is a special type of musical score – most typically for a solo instrument – which shows where to play the pitches on the given instrument rather than which pitches to produce, with rhythm indicated every bit well. Tablature is widely used in the 2000s for guitar and electrical bass songs and pieces in popular music genres such as rock music and heavy metallic music. This type of annotation was offset used in the late Middle Ages, and it has been used for keyboard (due east.g., pipe organ) and for fretted string instruments (lute, guitar).[two]

History [edit]

Outside modern eurocentric cultures exists a wide variety of systems of musical notation, each adjusted to the peculiar needs of the musical cultures in question, and some highly evolved classical musics do not employ notation at all (or but in rudimentary forms equally mnemonic aids) such as the khyal and dhrupad forms of Northern Republic of india. Western musical annotation systems describe only music adapted to the needs of musical forms and instruments based on equal temperament, but are ill-equipped to describe musics of other types, such every bit the ladylike forms of Japanese gagaku, Indian dhrupad, or the percussive music of ewe drumming. The infiltration of Western staff annotation into these cultures has been described by the musicologist Alain Daniélou[3] and others every bit a process of cultural imperialism.[4]

Precursors to sheet music [edit]

Musical notation was adult before parchment or newspaper were used for writing. The primeval form of musical note can exist found in a cuneiform tablet that was created at Nippur, in Sumer (today'due south Iraq) in almost 2000 BC. The tablet represents fragmentary instructions for performing music, that the music was composed in harmonies of thirds, and that it was written using a diatonic scale.[v]

A tablet from almost 1250 BC shows a more developed class of notation.[half dozen] Although the interpretation of the notation system is still controversial, it is articulate that the notation indicates the names of strings on a lyre, the tuning of which is described in other tablets.[vii] Although they are fragmentary, these tablets correspond the earliest notated melodies found anywhere in the world.[7]

The original rock at Delphi containing the 2d of the ii Delphic Hymns to Apollo. The music annotation is the line of occasional symbols above the main, uninterrupted line of Greek lettering.

Ancient Greek musical annotation was in employ from at least the 6th century BC until approximately the fourth century Advertizing; several complete compositions and fragments of compositions using this note survive. The notation consists of symbols placed in a higher place text syllables. An instance of a complete composition is the Seikilos epitaph, which has been variously dated betwixt the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD.

In ancient Greek music, 3 hymns by Mesomedes of Crete be in manuscript. One of the oldest known examples of music notation is a papyrus fragment of the Hellenic era play Orestes (408 BC) has been institute, which contains musical note for a choral ode. Ancient Greek notation appears to accept fallen out of use around the time of the Decline of the Roman Empire.

Western manuscript notation [edit]

Earlier the 15th century, Western music was written by hand and preserved in manuscripts, usually bound in large volumes. The best-known examples of Middle Ages music note are medieval manuscripts of monophonic chant. Chant notation indicated the notes of the chant tune, simply without whatsoever indication of the rhythm. In the case of Medieval polyphony, such as the motet, the parts were written in separate portions of facing pages. This process was aided by the advent of mensural notation, which also indicated the rhythm and was paralleled by the medieval practice of composing parts of polyphony sequentially, rather than simultaneously (every bit in after times). Manuscripts showing parts together in score format were rare and limited mostly to organum, especially that of the Notre Matriarch school. During the Middle Ages, if an Abbess wanted to have a copy of an existing composition, such as a limerick owned past an Abbess in another town, she would accept to hire a copyist to do the task by hand, which would be a lengthy process and one that could pb to transcription errors.

Even after the advent of music printing in the mid-1400s, much music continued to exist solely in composers' hand-written manuscripts well into the 18th century.

Printing [edit]

15th century [edit]

There were several difficulties in translating the new press printing technology to music. In the showtime printed book to include music, the Mainz Psalter (1457), the music notation (both staff lines and notes) was added in by hand. This is similar to the room left in other incunabulae for capitals. The psalter was printed in Mainz, Deutschland by Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer, and ane now resides in Windsor Castle and another at the British Library. Later, staff lines were printed, but scribes all the same added in the residual of the music by hand. The greatest difficulty in using movable type to print music is that all the elements must line up – the note head must be properly aligned with the staff. In vocal music, text must be aligned with the proper notes (although at this fourth dimension, even in manuscripts, this was not a high priority).

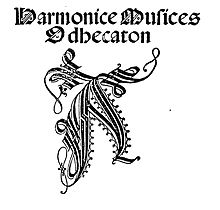

Music engraving is the art of drawing music note at high quality for the purpose of mechanical reproduction. The first machine-printed music appeared around 1473, approximately twenty years afterwards Gutenberg introduced the printing press. In 1501, Ottaviano Petrucci published Harmonice Musices Odhecaton A, which contained 96 pieces of printed music. Petrucci'southward press method produced clean, readable, elegant music, simply it was a long, difficult process that required three divide passes through the printing press. Petrucci later adult a process which required only two passes through the press. But it was however taxing since each pass required very precise alignment for the result to be legible (i.due east., and so that the note heads would be correctly lined upwardly with the staff lines). This was the first well-distributed printed polyphonic music. Petrucci as well printed the first tablature with movable type. Single impression printing, in which the staff lines and notes could exist printed in i pass, get-go appeared in London around 1520. Pierre Attaingnant brought the technique into broad use in 1528, and it remained trivial inverse for 200 years.

Frontispiece to Petrucci'south Odhecaton

A common format for issuing multi-part, polyphonic music during the Renaissance was partbooks. In this format, each voice-part for a collection of 5-role madrigals, for instance, would be printed separately in its own book, such that all five function-books would exist needed to perform the music. The same partbooks could be used by singers or instrumentalists. Scores for multi-function music were rarely printed in the Renaissance, although the use of score format as a means to etch parts simultaneously (rather than successively, as in the late Middle Ages) is credited to Josquin des Prez.

The effect of printed music was like to the issue of the printed word, in that data spread faster, more efficiently, at a lower price, and to more people than it could through laboriously manus-copied manuscripts. It had the additional issue of encouraging amateur musicians of sufficient means, who could now afford sheet music, to perform. This in many means affected the entire music industry. Composers could now write more music for amateur performers, knowing that it could be distributed and sold to the middle class.

This meant that composers did not have to depend solely on the patronage of wealthy aristocrats. Professional person players could have more than music at their disposal and they could admission music from different countries. It increased the number of amateurs, from whom professional players could then earn money by pedagogy them. Nonetheless, in the early on years, the toll of printed music limited its distribution. Another factor that limited the impact of printed music was that in many places, the right to print music was granted by the monarch, and merely those with a special impunity were immune to practice and so, giving them a monopoly. This was often an honour (and economic boon) granted to favoured court musicians or composers.

16th century [edit]

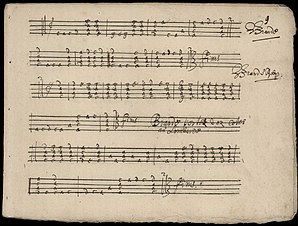

Example of 16th century canvass music and music notation. Excerpt from the manuscript "Muziek voor 4 korige diatonische cister".[eight]

Mechanical plate engraving was developed in the late sixteenth century.[9] Although plate engraving had been used since the early fifteenth century for creating visual art and maps, it was not applied to music until 1581.[9] In this method, a mirror paradigm of a complete page of music was engraved onto a metal plate. Ink was then applied to the grooves, and the music print was transferred onto paper. Metal plates could be stored and reused, which made this method an attractive option for music engravers. Copper was the initial metal of pick for early plates, but by the eighteenth century, pewter became the standard fabric due to its malleability and lower cost.[10]

Plate engraving was the methodology of option for music printing until the late nineteenth century, at which point its pass up was hastened by the development of photographic applied science.[9] Even so, the technique has survived to the present mean solar day and is still occasionally used past select publishers such every bit G. Henle Verlag in Germany.[xi]

As musical composition increased in complexity, so too did the applied science required to produce accurate musical scores. Unlike literary press, which mainly contains printed words, music engraving communicates several different types of information simultaneously. To be articulate to musicians, it is imperative that engraving techniques allow absolute precision. Notes of chords, dynamic markings, and other note line up with vertical accurateness. If text is included, each syllable matches vertically with its assigned melody. Horizontally, subdivisions of beats are marked not only past their flags and beams, but also by the relative infinite between them on the page.[9] The logistics of creating such precise copies posed several problems for early on music engravers, and take resulted in the development of several music engraving technologies.

19th century [edit]

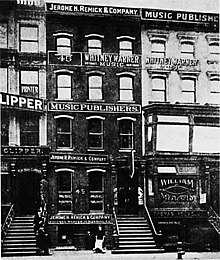

Buildings of New York City's Can Pan Alley music publishing district in 1910.[12]

In the 19th century, the music industry was dominated by sheet music publishers. In the U.s.a., the sheet music manufacture rose in tandem with blackface minstrelsy. The group of New York City-based music publishers, songwriters and composers dominating the industry was known as "Tin Pan Alley". In the mid-19th century, copyright control of melodies was not as strict, and publishers would often print their own versions of the songs pop at the time. With stronger copyright protection laws belatedly in the century, songwriters, composers, lyricists, and publishers started working together for their mutual financial benefit. New York Metropolis publishers full-bodied on vocal music. The biggest music houses established themselves in New York City, but pocket-size local publishers – often connected with commercial printers or music stores – connected to flourish throughout the country. An boggling number of East European immigrants became the music publishers and songwriters on Tin Pan Alley-the almost famous existence Irving Berlin. Songwriters who became established producers of successful songs were hired to be on the staff of the music houses.

The late-19th century saw a massive explosion of parlor music, with ownership of, and skill at playing the piano condign de rigueur for the middle-class family. In the late-19th century, if a middle-class family wanted to hear a popular new song or piece, they would purchase the canvas music and then perform the vocal or slice in an amateur fashion in their home. But in the early 20th century the phonograph and recorded music grew greatly in importance. This, joined by the growth in popularity of radio dissemination from the 1920s on, lessened the importance of the canvas music publishers. The record industry eventually replaced the sheet music publishers every bit the music industry'south largest force.

20th century and early on 21st century [edit]

In the belatedly 20th and into the 21st century, pregnant interest has adult in representing canvas music in a computer-readable format (see music annotation software), as well as downloadable files. Music OCR, software to "read" scanned canvass music then that the results can be manipulated, has been available since 1991.

In 1998, virtual canvass music evolved farther into what was to exist termed digital sheet music, which for the commencement time allowed publishers to make copyright sheet music available for purchase online. Unlike their hard copy counterparts, these files allowed for manipulation such as instrument changes, transposition and MIDI (Musical instrument Digital Interface) playback. The popularity of this instant commitment system among musicians appears to be interim as a catalyst of new growth for the industry well into the foreseeable hereafter.

An early computer notation program available for home computers was Music Construction Set, adult in 1984 and released for several different platforms. Introducing concepts largely unknown to the dwelling house user of the time, information technology allowed manipulation of notes and symbols with a pointing device such every bit a mouse; the user would "grab" a note or symbol from a palette and "driblet" information technology onto the staff in the correct location. The plan allowed playback of the produced music through various early sound cards, and could print the musical score on a graphics printer.

Many software products for modernistic digital audio workstation and scorewriters for general personal computers back up generation of sheet music from MIDI files, past a performer playing the notes on a MIDI-equipped keyboard or other MIDI controller or past transmission entry using a mouse or other computer device.

Past 1999, a organisation and method for analogous music display among players in an orchestra was patented past Harry Connick Jr.[13] Information technology is a device with a estimator screen which is used to show the sheet music for the musicians in an orchestra instead of the more than commonly used paper. Connick uses this system when touring with his big band, for instance.[14] With the proliferation of wireless networks and iPads similar systems have been adult. In the classical music earth, some string quartet groups use computer screen-based parts. In that location are several advantages to figurer-based parts. Since the score is on a calculator screen, the user tin can suit the contrast, brightness and even the size of the notes, to make reading easier. In add-on, some systems will practice "page turns" using a pes pedal, which means that the performer does non have to miss playing music during a page plow, equally oftentimes occurs with paper parts.

Of special practical interest for the general public is the Mutopia project, an endeavor to create a library of public domain canvass music, comparable to Project Gutenberg's library of public domain books. The International Music Score Library Projection (IMSLP) is too attempting to create a virtual library containing all public domain musical scores, besides as scores from composers who are willing to share their music with the world free of accuse.

Some scorewriter computer programs have a feature that is very useful for composers and arrangers: the ability to "play dorsum" the notated music using synthesizer sounds or virtual instruments. Due to the loftier cost of hiring a full symphony orchestra to play a new composition, before the evolution of these estimator programs, many composers and arrangers were but able to hear their orchestral works past arranging them for piano, organ or string quartet. While a scorewiter program'south playback will not incorporate the nuances of a professional orchestra recording, it nevertheless conveys a sense of the tone colors created past the slice and of the interplay of the different parts.

See also [edit]

- Choirbook, used for choral music during the Center Ages and Renaissance

- Eye motion in music reading

- List of Online Digital Musical Document Libraries

- Manuscript paper

- Musical notation

- Partbook, contains one part, mutual during the Renaissance and Baroque

- Music stand, a device that holds canvas music in position

- Scorewriter – music notation software

- Shorthand for orchestra instrumentation

References [edit]

- ^ Cochrane, Lalage (2001). "Open score". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan.

- ^ Hawkins, John (1776). A General History of the Science and Practice of Music (First ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing. p. 237. Retrieved iii May 2020.

- ^ Daniélou, Alain (2003). Sacred Music: Its Origins, Powers, and Future : Traditional Music in Today'south World. Varanasi, Bharat: Indica Books. ISBN8186569332. [ folio needed ]

- ^ Garofalo, Reebee (1993). "Whose World, What Beat: The Transnational Music Industry, Identity, and Cultural Imperialism". The Earth of Music. 35 (2): 16–32. JSTOR 43615564.

- ^ Kilmer, Anne D. (1986). "Old Babylonian Musical Instructions Relating to Hymnody". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. The American Schools of Oriental Research. 38 (i): 94–98. doi:ten.2307/1359953. JSTOR 1359953. S2CID 163942248.

- ^ Kilmer, Anne D. (21 April 1965). Güterbock, Hans G.; Jacobsen, Thorkild (eds.). "The Strings of Musical Instruments: their Names, Numbers, and Significance" (PDF). Assyriological Studies. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press. 16: 261–268.

- ^ a b West, M. L. (1994). "The Babylonian Musical Annotation and the Hurrian Melodic Texts". Music & Letters. Oxford Academy Press. 75 (2): 161–179. doi:x.1093/ml/75.2.161. JSTOR 737674.

- ^ "Muziek voor luit[manuscript]". lib.ugent.be . Retrieved 2020-08-27 .

- ^ a b c d King, A. Hyatt (1968). Four Hundred Years of Music Printing. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

- ^ Wolfe, Richard J. (1980). Early American Music Engraving and Printing. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- ^ "Music Engraving". Grand. Henle Publishers . Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- ^ "America's Music Publishing Industry – The story of Tin Pan Alley". The Parlor Songs Academy.

- ^ U.S. Patent six,348,648

- ^ "Harry Connick Jr. Uses Macs at Heart of New Music Patent". The Mac Observer. 2002-03-07. Retrieved 2011-11-15 .

External links [edit]

Athenaeum of scanned works [edit]

- IMSLP – Public domain canvas music library of PDF files, International Music Score Library Project

- Music for the Nation – American sail music annal, Library of Congress

- Historic American Sheet Music – Knuckles University Libraries Digital Collections, more than 3000 pieces of sheet music published in the United States betwixt 1850 and 1920.

- Lester Southward. Levy Sheet Music Collection – sheet music projection of The Sheridan Libraries of Johns Hopkins Academy.

- Pacific Northwest Sheet Music Collection, Academy of Washington Libraries

- IN Harmony: Canvas Music from Indiana, sail music from the Indiana University Lilly Library, the Indiana Land Library, the Indiana State Museum, and the Indiana Historical Order.

- Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki) – free canvass music archive with emphasis on choral music; contains works in PDF and also other formats.

- Mutopia project – gratis canvas music archive in which all pieces have been newly typeset with GNU LilyPond equally PDF and PostScript.

- Project Gutenberg – sheet music section of Project Gutenberg containing works in Finale or MusicXML format.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sheet_music

0 Response to "as you read, note what each program or law did or was intended to do"

Post a Comment